„Když zvoláš Slovan, nechť se ti ozve člověk!“

(Ján Kollár, Básně)

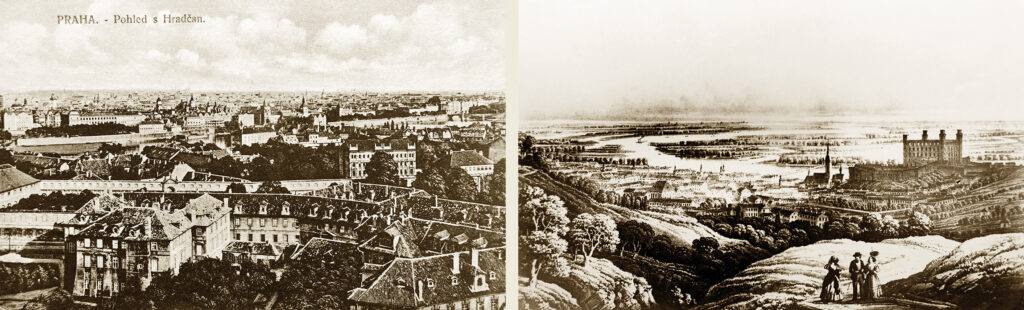

Búrlivé 19. storočie možno označiť tiež ako obdobie utvárania moderných slovanských národov v strednej Európe. „Sloboda, rovnosť, bratstvo,“ tri obyčajné slová tvoriace heslo francúzskej revolúcie, priniesli začiatkom 19. storočia do strednej Európy idey humanizmu, demokracie a národnej slobody. V období formovania novej občianskej spoločnosti ich vyznávanie, zdôrazňovanie a hlásanie v národnoobrodeneckom procese stalo sa príznačnou črtou, najmä v živote a hnutiach neslobodných národov vystavených stupňujúcemu sa nacionálnemu, sociálnemu a kultúrnemu útlaku. Tri obyčajné slová stali sa dôležitou morálnou oporou i zbraňou národnoobranných a emancipačných úsilí v období pred revolučným rokom 1848. Ján Kollár stojí na začiatku tohto úsilia, je jeho vedúcou osobnosťou i tvorcom mnohých základných ideí rozvíjajúceho sa národného hnutia slovanských národov. Do povedomia súčasníkov sa zapísal ako mimoriadne všestranná osobnosť. Bol básnikom, prozaikom, filozofom či slavistom, zberateľom ľudovej slovesnosti a jazykovedcom, ale aj evanjelickým kňazom, kazateľom, teológom a na sklonku života profesorom na viedenskej univerzite. Na literárnom poli vytvoril nezabudnuteľné dielo naplnené básnickými zbierkami, memoárovou a cestopisnou literatúrou, rozsiahlymi teoretickými spismi z oblasti slovanskej archeológie, histórie a jazykovedy, náboženskou spisbou, zbierkami ľudovej slovesnosti, prácami o slovanskej vzájomnosti. Práve myšlienka slovanskej vzájomnosti, ktorá sa prelína celým Kollárovým životom, jeho vedeckým, kultúrnym a umeleckým pôsobením, ktorú možno označiť za východiskovú myšlienku jeho politickej a kultúrnej koncepcie, patrila k jednej zo základných ciest, po ktorých sa vydal proces slovenského národného obrodenia. Najväčší dosah na aktivizáciu národnoobrodeneckého hnutia slovanských národov zaznamenalo jeho básnické dielo, predovšetkým Slávy dcera, ktorá je prejavom ideológie jednotného slovanského národa – Všeslávie.

„When you cry Slav, let a man answer you!“

(Ján Kollár, Poems)

The turbulent 19th century can be also described as a period of the formation of modern Slavic nations in the Central Europe. „Liberty, Equality, Fraternity“, the three ordinary words that defined the French Revolution, brought the ideas of humanism, democracy and national freedom to the Central Europe in the early 19th century. In the formative period of the new civil society, recognition, emphasis and proclamation of these values characterised the process of the national revival, especially in the lives and movements of enslaved nations subjected to escalating national, social and cultural oppression. These three ordinary words meant a significant moral support and weapon of national defence and emancipatory efforts in the period before the revolutionary year of 1848. Ján Kollár, a leading personality and the creator of many of the basic ideas of the developing national movement of the Slavic nations, stood at the very beginning of these efforts . He was respected as an extremely versatile personality by his contemporaries. Not only was he a poet, prose writer, philosopher and Slavist, a collector of folklore and linguist, but he was also an evangelical pastor, preacher, theologian and, towards the end of his life, a professor at the University of Vienna, too. In the literature, he created an unforgettable body of work filled with poetry collections, memoirs and travel literature, extensive theoretical writings on Slavic archaeology, history and linguistics, religious writings, collections of folklore and works on Slavic reciprocity. The idea of the Slavic reciprocity, which permeates the whole of Kollár’s life, his scientific, cultural and artistic activity and which can be described as the starting point of his political and cultural conception, was one of the essential paths followed throughout the process of the Slovak national revival. The greatest impact on the activation of the national revival movement of the Slavic nations was made by his poetic works, especially The Daughter of Sláva, which is a manifestation of the ideology of a unified Slavic nation – Panslavism.

„Wenn du einen Slawen rufst, soll dir ein Mensch antworten!“

(Ján Kollár, Gedichte)

Die turbulente Epoche des 19. Jahrhunderts kann auch als Zeit der Formung moderner slawischer Nationen in Mitteleuropa bezeichnet werden. „Freiheit, Gleichheit, Brüderlichkeit“, drei einfache Worte, die das Motto der Französischen Revolution bildeten, brachten zu Beginn des 19. Jahrhunderts Ideen des Humanismus, der Demokratie und der nationalen Freiheit nach Mitteleuropa. In der Zeit der Formung einer neuen bürgerlichen Gesellschaft wurden ihre Verkündung, Betonung und Verbreitung im Prozess der nationalen Wiedergeburt zu einem charakteristischen Merkmal, insbesondere im Leben und in den Bewegungen der unfreien Nationen, die einem zunehmenden nationalen, sozialen und kulturellen Unterdruck ausgesetzt waren. Diese drei einfachen Worte wurden zu einer wichtigen moralischen Stütze und einem Instrument der nationalen Verteidigungs- und Emanzipationsbestrebungen in der Zeit vor dem revolutionären Jahr 1848. Ján Kollár stand am Anfang dieser Bemühungen, er war eine führende Persönlichkeit und Schöpfer vieler grundlegender Ideen der sich entwickelnden nationalen Bewegung der slawischen Völker. Er prägte das Bewusstsein seiner Zeitgenossen als eine außergewöhnlich vielseitige Persönlichkeit. Er war Dichter, Prosaist, Philosoph oder Slawist, Sammler von Volksliteratur und Linguist, aber auch evangelischer Priester, Prediger, Theologe und gegen Ende seines Lebens Professor an der Universität Wien. Im literarischen Bereich schuf er ein unvergessliches Werk, das mit Gedichtsammlungen, Memoiren- und Reiseliteratur, umfangreichen theoretischen Schriften aus dem Bereich der slawischen Archäologie, Geschichte und Linguistik, religiösen Schriften, Sammlungen von Volksliteratur, Arbeiten über slawische Gegenseitigkeit gefüllt war. Gerade die Idee der slawischen Gegenseitigkeit, die sich durch Kollárs gesamtes Leben, seine wissenschaftliche, kulturelle und künstlerische Tätigkeit zog, die als Ausgangspunkt seiner politischen und kulturellen Konzeption angesehen werden kann, gehörte zu den Grundwegen, auf denen der Prozess der slowakischen nationalen Wiedergeburt voranschritt. Den größten Einfluss auf die Aktivierung der nationalen Wiedergeburtsbewegung der slawischen Völker hatte sein poetisches Werk, insbesondere die „Tochter der Sláva“, die ein Ausdruck der Ideologie eines einheitlichen slawischen Volkes – des Pan-Slawismus ist.

OSUDOVÁ LÁSKA JÁNA KOLLÁRA

„Život nadobúda krásu a ozajstnú hodnotu len vtedy, keď sa stane poetickým prostredníctvom ideálov lásky a priateľstva. Tomuto poslednému venuje aj túto pamiatku Váš priateľ Ján Kollár z Uhorska“

(Zápis Jána Kollára v Pamätníku Friederiky Schmidtovej 13. 9. 1818)

Život Jána Kollára dramaticky poznamenali dva roky pobytu na univerzite v Jene v rokoch 1817 – 1819. Tu dozrel ideovo, filozoficky, ale aj ľudsky. Jeho život sa naplnil množstvom citových zážitkov. Impulzom sa stala intenzívne prežívaná láska k dcére evanjelického farára v Lobede Johanne Auguste Friederike Schmidtovej. Citové vzplanutie zanechalo v básnikovi hlboké stopy a malo dosah i stálu ozvenu. Vo svojej autobiografii predstavil Kollár svoj vzťah k Friederike Schmidtovej vecne a bez väčšieho citového vzrušenia. Korešpondencia medzi ním a Friederikou dokazuje, že citové vzplanutie bolo spontánne. Malo dramatický priebeh, zápletku v prvotnej životnej nenaplnenosti tohto vzťahu i sentimentálny koniec. „Nechcem Vás vábiť nijakými rečičkami. Veď moju vlasť dobre poznáte. Nie je to nijaký raj, nie je to nijaká pustatina. Vzdelanosť sa trblieta ešte len v rannej kráse. Nie vždy sa u nás nájdu hlavy, ale srdcia, ľudia istotne.“ – opísal v liste svoju vlasť Kollár milovanej Friederike. To však nestačilo. Bola tu čerstvo ovdovená matka, ktorá odmietla pustiť svoju najstaršiu dcéru do vzdialeného a neznámeho Uhorska. Zdá sa, že skutočná láska Jána Kollára k jej dcére ostala pred ňou dosť utajená. Koncom marca 1819 krátko po odchode z Jeny píše Kollár svojmu „zbožňovanému anjelovi“ priznanie, že by z lásky k nej opustil svoju vlasť a usadil sa v jej kraji. A pokračuje: „…musím sa priznať: miloval som Vás, milujem Vás, budem Vás večne milovať v pravom slova zmysle.“ Korešpondencia medzi zaľúbencami, spočiatku tak intenzívna, sa prerušila. Po štyroch rokoch odmlky sa Friederika ozvala. Na otázku „nezabudnuteľnej priateľky a sestry“ či sa oženil, odpovedal: „…moja žena sa vola Rezi-gná-cia, po nemecky odriekanie.“ Rok 1834 priniesol zásadnú zmenu do života Jána Kollára. Dozvedel sa, že Friederika Schmidtová, jeho osudová láska, ktorú mylne považoval za mŕtvu, je zdravá a žije v Jene. Mína žije!!! Pocit rezignácie vystriedali pocity radosti a šťastia. „Teraz si Ty moja a ja Tvoj“ – píše Kollár z Pešti 27. augusta 1835 „svojmu anjelovi“. Po vyše šestnástich rokoch odlúčenia, ospevovaná Mína, s ktorou ako vulkán prešiel celým slovanským svetom, zostúpila do básnikovho života 22. septembra 1835 ako jeho zákonitá manželka.

THE FATAL LOVE OF JÁN KOLLÁR

Ján Kollár’s life was dramatically marked by two years spent at the University of Jena in 1817 – 1819. Here he matured ideologically, philosophically and as a human being. His life was filled with many emotional experiences. The impetus was the intensely felt love for Johanna Auguste Friederike Schmidt, the daughter of the evangelical pastor in Lobeda. The emotional outburst left deep traces in the poet and had a lasting impact on him. In his autobiography, Kollár described his relationship with Friederike Schmidt rationally and without any greater emotional involvement. However, the correspondence between him and Friederike proves that it was spontaneous. It had a dramatic course, a plot in the early failure to fulfil the relationship and a sentimental ending, too. „I don’t want to tempt you with any cheap talk. After all, you know my homeland well. It is no paradise, but no wilderness either. Education glitters only in its early beauty. There are not always smart heads there, but hearts, people surely.“, as Kollár described his homeland in a letter to his beloved Friederike. Unfortunately, this was not enough. There was her newly widowed mother who refused to let her eldest daughter leave for the distant and unknown Hungary. It appears that the true love of Jan Kollár for her daughter remained unknown to her. At the end of March 1819, shortly after leaving Jena, Kollár wrote to his „adored angel“ confessing that he would leave his homeland and settle in her region out of love for her. He continued, „…I must confess I have loved you, I love you, I will love you eternally in the true sense of the word.“ The correspondence between the lovers, at first so intense, was interrupted. After four years of silence, Friederike contacted him. Asked by his „unforgettable friend and sister“ whether he had married, he replied: „…my wife’s name is Resig-na-tion, renunciation in German.“ The year 1834 meant a fundamental turn in the life of Ján Kollár. He learned that Friederike Schmidt, his ill-fated love, whom he had mistakenly thought to be dead, was well and living in Jena. Mína is alive!!! Feelings of resignation were replaced by feelings of joy and happiness. „Now you are mine and I am yours“, he wrote from Pest on 27th of August 1835 „to his angel“. After more than sixteen years of separation, the celebrated Mína, with whom he had traversed the whole Slavic world like a volcano, descended into the poet’s life on 22nd of September 1835 as his lawful wife.

SCHICKSALHAFTE LIEBE VON JÁN KOLLÁR

Das Leben von Ján Kollár wurde durch den zweijährigen Aufenthalt an der Universität Jena in den Jahren 1817–1819 dramatisch geprägt. Hier reifte er ideologisch, philosophisch, aber auch als Mensch. Sein Leben war voller emotionaler Erfahrungen. Den Anstoß gab die intensiv erlebte Liebe zu Johanna Augusta Friederike Schmidt, der Tochter des evangelischen Pfarrers in Lobed. Der Gefühlsausbruch hinterließ tiefe Spuren im Dichter und hatte ein bleibendes Echo. In seiner Autobiografie schilderte Kollár seine Beziehung zu Friederika Schmidt sachlich und ohne große emotionale Aufregung. Der Briefwechsel zwischen ihm und Friederika beweist, dass der Gefühlsausbruch spontan erfolgte. Es hatte einen dramatischen Verlauf, eine Handlung im anfänglichen Leben, eine unerfüllte Beziehung und ein sentimentales Ende. „Ich möchte dich nicht mit Worten verführen. Schließlich kennen Sie meine Heimat gut. Es ist kein Paradies, es ist kein Ödland. Bildung funkelt immer noch in der Schönheit des Morgens. Wir finden nicht immer Köpfe, aber sicher Herzen, Menschen.“ – Kollár beschrieb seiner geliebten Friederika in einem Brief seine Heimat. Aber das war nicht genug. Es gab eine frisch verwitwete Mutter, die sich weigerte, ihre älteste Tochter in das ferne und unbekannte Ungarn gehen zu lassen. Es scheint, dass Ján Kollárs wahre Liebe zu ihrer Tochter vor ihr ein Geheimnis blieb. Ende März 1819, kurz nachdem er Jena verlassen hatte, schrieb Kollár seinem „verehrten Engel“ ein Geständnis, dass er aus Liebe zu ihr seine Heimat verlassen und sich in ihrer Region niederlassen würde. Und er fährt fort: „…Ich muss gestehen: Ich habe dich geliebt, ich liebe dich, ich werde dich im wahrsten Sinne des Wortes für immer lieben.“ Der zunächst so intensive Briefwechsel zwischen den Liebenden wurde unterbrochen. Nach vier Jahren des Schweigens meldete sich Friederika zu Wort. Auf die Frage seiner „unvergesslichen Freundin und Schwester“, ob er verheiratet sei, antwortete er: „…der Name meiner Frau ist Rezi-gná-cia, nach der deutschen Entsagung.“ Das Jahr 1834 brachte eine grundlegende Veränderung in Ján Kollárs Leben erfuhr, dass Friederika Schmidtová, seine schicksalhafte Liebe, die er fälschlicherweise für tot hielt, in Jena lebendig und wohlauf ist!!! Das Gefühl der Resignation ist durch Gefühle der Freude und des Glücks ersetzt worden – schreibt Kollar am 27. August 1835 aus Pest. zu einem Engel“. Nach mehr als sechzehn Jahren der Trennung trat die berühmte Mína, mit der er die gesamte slawische Welt bereiste, am 22. September 1835 als seine rechtmäßige Frau in das Leben des Dichters ein.

SLÁWY DCERA

„Láska jest všech velkých skutků zárod, a kdo nemiloval, nemůže ani znáti, co je vlast a národ!“

(Ján Kollár, Slávy dcera, 1832)

Básnicky začal Ján Kollár tvoriť počas pobytu v Jene, kde študoval. K tvorbe ho inšpirovali viaceré skutočnosti, ako o tom svedčí tematické zloženie jeho prvej básnickej zbierky, ktorá vyšla v roku 1821 v Prahe pod názvom Básně Jana Kollára. Významným inšpiračným zdrojom Kollárovej básnickej prvotiny bola osobnosť Friederiky Schmidtovej, ktorú básnik neskoršie pretvoril do obrazu monumentálnej ženskej symboliky slovenskej a slovanskej poézie, do podoby Míny. Kollárova milá z čias jeho jenských štúdií, osobitne silným putom lásky evokovala v Kollárovi horúci cit, ktorý nemohol nevyorať hlbokú brázdu v jeho poézii a ktorý pokolenia čitateľov spoznávali v skladbe Slávy dcera. Okrem ľúbostných zneliek zbierka obsahuje skladby reflektujúce súdobú národno – spoločenskú a kultúrnu situáciu. Básne s vlasteneckou tematikou, elégie, ódy a epigramy dokresľovali portrét básnickej osobnosti Kollára – rebela.

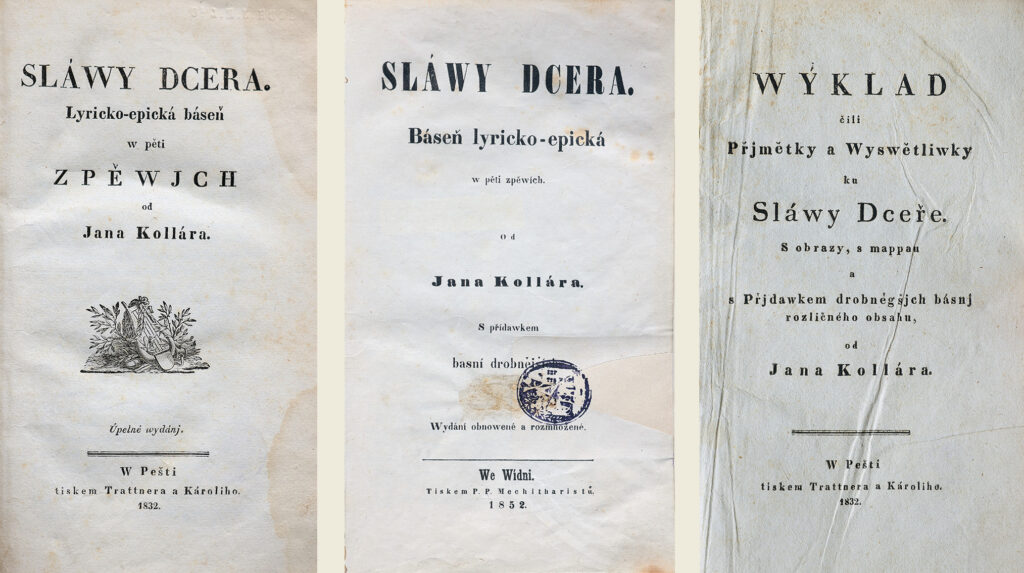

Básně sa stali východiskom básnickej skladby Sláwy dcera we třech zpěvjch, ktorá vyšla v Budíne 1824 označená ako druhé vydanie. Jadrom básnickej skladby sa stalo 86 zneliek z cyklu Znělky neb sonety, ktoré Kollár rozšíril o tie, ktoré nemohli byť kvôli zásahu cenzúry v roku 1821 publikované. Pôvodné vydanie skladby tvorí Předzpěv v elegickom distichu a 150 zneliek rovnomerne rozdelených do troch spevov označených podľa riek symbolizujúcich slovanské kraje, ktorými básnik putuje: Zála (symbolizujúca Nemecko – vlasť básnikovej milej), Labe (symbolizujúce Čechy) a Dunaj (symbolizujúci Kollárovu vlasť – Slovensko). Obrys tejto cesty tvorí pozadie pre množstvo básnických reflexií o láske a kráse, o človeku, o morálke, vlastenectve, o slávnej minulosti a trpkej prítomnosti slovanských národov i vízií o ich lepšej budúcnosti. K básnickej skladbe sa Ján Kollár neustále vracal, dopĺňal ju a rozširoval. Po vydaní v roku 1824, nasledovali v rokoch 1832, 1845 a 1852 jej ďalšie rozšírené a doplnené verzie.

THE DAUGHTER OF SLÁVA

Ján Kollár began to write poetry while studying in Jena. He drew inspiration from various sources as evidenced by the thematic composition of his first collection of poetry published in Prague in 1821 titled The Poems of Ján Kollár. The personality of Friederike Schmidt, whom, in the form of Mína, the poet later transformed into the image of the monumental female symbol of Slovak and Slavic poetry, served as an important source of inspiration for his first poetic work. Kollár’s sweetheart from the time of his Jena studies, with a particularly strong bond of love, evoked in him a burning emotion that could not but leave a deep trace in his poetry, which generations of his readers have come to know in the composition of The Daughter of Sláva. In addition to love songs, the collection contains compositions reflecting the contemporary national, social and cultural situation. Poems with patriotic themes, elegies, odes and epigrams illustrated the portrait of Kollár’s poetic personality – the rebel.

The Poems became the source of the poetic composition The Daughter of Sláva in Three Songs published in Buda in 1824 as the second edition. Eighty-six tunes from The Tunes or Sonnets, which Kollár added to the ones that could not be published due to the intervention of the censors back in 1821, formed the core of the poetic composition. The original edition of the composition consists of The Prelude in elegiac distich and 150 tunes evenly divided into three songs named after the rivers symbolizing the Slavic regions through which the poet travels: Saale (a symbol of Germany – the homeland of the poet’s beloved), Elbe (a symbol of Bohemia) and Danube (a symbol of Kollár’s homeland – Slovakia). The outline of this journey forms the background for several poetic reflections on love and beauty, man, morality, patriotism, the glorious past and the bitter present of the Slavic nations, as well as visions of their better future. Ján Kollár kept constantly returning to his poetic composition, supplemented and expanded it. After its publication in 1824, it was followed in 1832, 1845 and 1852 by further expanded and enlarged versions.

TOCHTER DER SLÁVA

Ján Kollár begann während seines Aufenthalts in Jena, wo er studierte, Gedichte zu schreiben. Verschiedene Fakten inspirierten ihn, wie das thematische Zusammensetzung seiner ersten Gedichtsammlung zeigt, die 1821 in Prag unter dem Titel „Básně Jana Kollára“ erschien. Eine bedeutende Inspirationsquelle für Kollárs poetisches Erstlingswerk war die Persönlichkeit von Friederika Schmidt, die der Dichter später in das Bild der monumentalen weiblichen Symbolik der slowakischen und slawischen Poesie, in die Gestalt von Mína, verwandelte. Kollárs Geliebte aus seiner Jenaer Studienzeit, besonders durch ein starkes Band der Liebe, erweckte in Kollár eine heiße Empfindung, die eine tiefe Furche in seiner Poesie ziehen musste und die Generationen von Lesern in der Komposition Tochter der Sláva kennenlernen würden. Neben Liebesliedern enthält die Sammlung Kompositionen, die die zeitgenössische nationale – gesellschaftliche und kulturelle Situation reflektieren. Gedichte mit patriotischer Thematik, Elegien, Oden und Epigramme skizzierten das Porträt der poetischen Persönlichkeit Kollárs – des Rebellen.

Die Gedichte wurden zur Grundlage der poetischen Komposition Tochter der Sláva in drei Gesängen, die 1824 in Ofen als zweite Ausgabe erschien. Der Kern der poetischen Komposition bestand aus 86 Liedern aus dem Zyklus Znělky neb sonety, die Kollár um jene erweiterte, die 1821 aufgrund der Zensur nicht veröffentlicht werden konnten. Die ursprüngliche Ausgabe der Komposition besteht aus einem Vorspiel im elegischen Distichon und 150 gleichmäßig auf drei Gesänge verteilten Liedern, die nach Flüssen benannt sind, die slawische Länder symbolisieren, durch die der Dichter reist: Zála (symbolisiert Deutschland – das Heimatland der Dichters Geliebten), Elbe (symbolisiert Böhmen) und Donau (symbolisiert Kollárs Heimatland – die Slowakei). Der Umriss dieser Reise bildet den Hintergrund für eine Vielzahl poetischer Reflexionen über Liebe und Schönheit, über den Menschen, über Moral, Patriotismus, über die ruhmreiche Vergangenheit und die bittere Gegenwart der slawischen Völker sowie Visionen über ihre bessere Zukunft. Ján Kollár kehrte ständig zur poetischen Komposition zurück, ergänzte und erweiterte sie. Nach der Veröffentlichung im Jahr 1824 folgten in den Jahren 1832, 1845 und 1852 weitere erweiterte und ergänzte Versionen.

BIOGRAFICKÉ KALENDÁRIUM JÁNA KOLLÁRA (1793 – 1852)

1793 – 29. júla narodil sa Ján Kollár v Mošovciach

1800 – 1806 – navštevoval ľudovú školu v Mošovciach

1806 – 1809 – študoval na nižšom gymnáziu v Kremnici

1810 – 1812 – študoval na gymnáziu v Banskej Bystrici

1812 – 1815 – študoval filozofiu a teológiu na ev. lýceu v Bratislave

1815 – 1817 – pôsobil ako vychovávateľ v Banskej Bystrici

1817 – 1819 – študoval teológiu na univerzite v Jene

1818 – v marci zoznámil sa s Friederikou Schmidtovou na fare v Lobede

1819 – 1848 – pôsobil ako kaplán, neskôr farár slovenskej ev. cirkvi v Pešti

1821 – vydal v Prahe zbierku Básně Jana Kollára

1824 – v Budíne vyšla zbierka Sláwy dcera we třech zpěwjch od Jana Kollára

1832 – v Pešti vyšla Sláwy dcera. Báseň lyricko-epická w pěti zpěwích od Jana Kollára

1835 – 22. septembra sa Kollár oženil s Friederikou Schmidtovou

1837 – 17. februára sa Kollárovi narodila dcéra Ľudmila

1849 – mimoriadny profesor archeológie na univerzite vo Viedni

1852 – 24. januára J. Kollár zomrel vo Viedni, pochovaný na cintoríne sv. Marka vo Viedni

1904 – telesné pozostatky J. Kollára boli prevezené z Viedne do Prahy

BIOGRAPHICAL CALENDAR OF JÁN KOLLÁR (1793 – 1852)

1793 – Ján Kollár was born in Mošovce on 29th of July

1800 – 1806 – attended the folk school in Mošovce

1806 – 1809 – studied at the lower grammar school in Kremnica

1810 – 1812 – graduated from the grammar school in Banská Bystrica

1812 – 1815 – studied philosophy and theology at the Evangelical Lyceum in Bratislava

1815 – 1817 – worked as an educator in Banská Bystrica

1817 – 1819 – studied theology at the University of Jena

1818 – in March he met Friederike Schmidt at the parish in Lobeda

1819 – 1848 – worked as a chaplain, later as a pastor of the Slovak Evangelical Church in Pest

1821 – published his collection of Poems of Ján Kollár in Prague

1824 – the collection The Daughter of Sláva in Three Songs by Ján Kollár was published in Buda

1832 – The Daughter of Sláva, Lyric-Epic Poem in Five Songs by Jan Kollár was published in Pest

1835 – J. Kollár married Friederike Schmidt on 22nd of September

1837 – Kollár’s daughter Ľudmila was born 17th of February

1849 – named an Associate Professor of Archaeology at the University of Vienna

1852 – J. Kollár died in Vienna on 24th of January, buried in St. Mark’s Cemetery in Vienna

1904 – the remains of J. Kollár were transported from Vienna to Prague

Birth house of Ján Kollár

BIOGRAPHISCHER KALENDER VON JÁN KOLLÁR (1793 – 1852)

1793 – Geboren am 29. Juli: Ján Kollár in Mošovce

1800 – 1806 – Besuchte die Volksschule in Mošovce

1806 – 1809 – Besuchte das Gymnasium in Kremnica

1810 – 1812 – Abschluss des Gymnasiums in Banská Bystrica

1812 – 1815 – Studierte Philosophie und Theologie am Evangelischen Lyzeum in Bratislava

1815 – 1817 – Tätig als Erzieher in Banská Bystrica

1817 – 1819 – Studierte Theologie an der Universität in Jena

1818 – Im März machte er die Bekanntschaft mit Friederika Schmidt auf dem Pfarrhof in Lobeda

1819 – 1848 – Wirkte als Kaplan, später als Pfarrer der Slowakischen Evangelischen Kirche in Pest

1821 – Veröffentlichte in Prag die Gedichtsammlung „Básně Jana Kollára“

1824 – In Budín erschien die Sammlung „Tochter der Sláva in drei Gesängen“ von Ján Kollár

1832 – In Pest erschien „Tochter der Sláva. Lyrisch-episches Gedicht in fünf Gesängen“ von Ján Kollár

1835 – Am 22. September heiratete J. Kollár Friederika Schmidt

1837 – Am 17. Februar wurde Kollárs Tochter Ľudmila geboren

1849 – Außerordentlicher Professor für Archäologie an der Universität Wien

1852 – Am 24. Januar starb J. Kollár in Wien, begraben auf dem St. Markus-Friedhof in Wien

1904 – Die sterblichen Überreste von J. Kollár wurden von Wien nach Prag überführt

Aj zde leží zem ta, před okem mým smutně slzícím,

někdy kolébka, nyní národu mého rakev.

Stůj, noho, posvátné místa jsou, kamkoli kráčíš,

k obloze, Tatry synu, vznes se, vyvýše pohled.

Neb raději k velikému přiviň tomu tam se dubisku,

jenž vzdoruje zhoubným až dosaváde časům.

Však horší je času vzteklosti člověk, jenž berlu železnou

v těchto krajích na tvou, Slávie, šíji chopil.

Horší nežli divé války, hromu, ohně divější,

zaslepenec, na své když zlobu plémě kydá.

Ó, věkové dávní, jako noc vůkol mne ležící,

ó krajino všeliké slávy i hanby plná!

Od Labe zrádného k rovinám až Visly nevěrné,

od Dunaje k hltavým Baltu celého pěnám,

krásnohlasý zmužilých Slovanů kde se někdy ozýval,

aj oněměl již, byv k ourazu zášti, jazyk.

A kdo se loupeže té volající vzhůru dopustil?

Kdo zhanobil v jednom národu lidstvo celé?

Zardi se, závistná Teutonie, sousedo Slávy,

tvé vin těchto počet spáchaly někdy ruky.

Sám svobody kdo hoden, svobodu zná vážiti každou,

ten, kdo do pout jímá otroky, sám je otrok.

Ajhľa, tu leží tá zem – keď vidím ju, slzy mi tečú,

kolískou národa môjho bývala – rakvou je dnes.

Stoj, noha! Posvätné miesta sú všade, nech kamkoľvek vkročíš,

k oblohe, ó, syn Tatry, sa vznes, keď pozdvihneš zrak.

Alebo radšej sa priviň tam k tomu veľkému dubu,

vzdorujúcemu dosiaľ zhubnému hlodaniu čias.

Horší než besnenie času je človek, čo železnou berlou

núti ťa v týchto krajoch, Slávia, zohýnať driek.

Horší než divé vojny a divší než oheň a hromy

zaslepenec, čo chrlí nenávisť na vlastný kmeň.

Ó, dávne veky, čo vôkol mňa ležíte, podobné noci,

krajina plná slávy, ale i hanby a bied!

Od zradnej rieky Labe až k rovinám nevernej Visly,

od Dunaja až po ten hltavo spenený Balt

kedysi krásnohlasá reč mužných Slovanov znela,

oj, už ju nemá, už zloba zlomila kruto jej hlas.

A kto má na svedomí to zbojstvo, čo do nebies volá?

Kto v jednom národe takto zhanobil človečí rod?

Zapýr sa Teutónia, ty žiarlivá suseda Slávy,

robotou tvojich rúk je každá z prastarých vín.

Kto sám je slobody hoden, aj slobodu iných si váži,

kto iných zotročuje, otrokom stáva sa tiež.

PŘEDZPĚV

„Čas vše mění, i časy, k vítězství on vede pravdu“

Předzpěv je príhovorom do duše národa, mohutnou elegickou nostalgiou nad osudom Slovanov, v ktorej sa striedajú elegické tóny smútku s patetickými a rapsodickými výzvami k činu na „národu roli dedičnej.“ Do protikladu je tu postavená ich slávna minulosť a neradostná prítomnosť. Hneď prvé dva verše: rozsiahle ponemčené oblasti niekdajších polabských Slovanov, kedysi kolíska, teraz rakva pôvodne tam sídliacich národov, nad ktorými nemožno nezaplakať – hneď tento vstup ohlasuje program a tón skladby. Slovanský svet sa prezentuje ako ponížená, zotročená a dlhodobo kolonizovaná periféria západného, najmä germánskeho sveta. Básnik pranieruje zotročiteľa, „závistnú Teutóniu“, teda Nemecko, ktoré sa voči nim dopustilo mnohých neprávostí. „Zardi se, závistná Teutonie, sousedo Slávy, tvé vin těchto počet spáchaly někdy ruky.“ Odpoveďou na obžalobu germánskej expanzie je pasáž o spravodlivosti – oslava slobody, ktorá najintenzívnejšie rezonuje v dvojverši: „Sám svobody kdo hoden, svobodu zná vážiti každou, ten, kdo do pout jímá otroky, sám je otrok.“ Pre básnika úhlavnými nepriateľmi Slovanov sú Nemci, druhí Slovania – odrodilci. Ľudia zaslepení, nečistí, falošní, nehodní svojho mena. Nádejou pre budúcnosť Slovanov je Rusko, symbolizované motívom duba, okolo ktorého by sa mali podľa neho zomknúť všetky slovanské národy. Elegické gestá v skladbe postupne nahrádza viera v humanistickú budúcnosť ľudstva, apelatívna výzva k činu a vizionárska obraznosť: „Největší je neřest v neštěstí láti neřestem, ten, kdo kojí skutkem hněv nebe, lépe činí.“ Slovanom zostáva ešte budúcnosť: sebapoznanie, kultúrna a pevná viera, že čas, ktorý spôsobuje rany, tiež ich lieči, že ak blúdi národ, nemôže zblúdiť celé ľudstvo. „Čas vše mění, i časy, k vítězství on vede pravdu, co sto věků bludných hodlalo, zvrtne doba“ – ľudstvo si nájde pravú cestu a po sto bludných rokoch sa zmení čas a zvrtne doba – zaprorokoval Kollár – prorok. V tejto nádeji uzatvárajú sa distichá Předzpěvu.

PRELUDE

Prelude is an address to the soul of the nation, a powerful elegiac nostalgia for the fate of the Slavs, in which elegiac tones of sadness alternate with pathetic and rhapsodic calls to action on „the nation’s hereditary role“. Their glorious past and joyless present are juxtaposed here. The very first two verses: the vast Germanised areas of the former Slavs of the Elbe, once the cradle, now the coffin of the nations originally settled there, over which it is impossible not to weep. This entrée instantly sets the agenda and tone of Prelude. The Slavic world is presented as a humiliated, enslaved and long-colonised periphery of the Western, mainly Germanic world. The poet denounces the enslavers, the „envious Teutonia“, i.e., Germany, which has committed many injustices against them. „Beware, envious Teutonia, neighbour of Sláva, thy guilt of these counts has ever committed hands.“ The response to the indictment of Germanic expansion is a passage about justice – a celebration of freedom that resonates most intensely in the couplet, „He, who is worthy of freedom, knows how to respect each one; he who shackles slaves is himself a slave.“ For the poet, the Germans represent the main enemies of the Slavs, the other Slavs – the renegades. People blinded, impure, false, unworthy of their name. Russia, symbolised by the motif of the oak tree, around which, in his opinion, all Slavic people should unite, is the hope for the future of the Slavs. The elegiac gestures in the composition are gradually replaced by a belief in the humanistic future of mankind, an appeal to action and visionary imagery: „The greatest vice in misfortune is love of vice, the one who nurses by deed the wrath of heaven does better.“ The Slavs still have a future: self-knowledge, a cultural and firm belief that time, which causes wounds, also heals them, that if a nation goes astray, it cannot lead all mankind astray. „Time changes everything, even times, it leads the truth to victory, what a hundred erroneous ages intended, time reverses.“ – Mankind will find the true path and after a hundred wandering years, time will change and the times will turn, Kollár prophesied. In this hope the distiches of the Prelude conclude.

VORWORT

Das Vorspiel ist ein Appell an die Seele der Nation, eine kraftvolle elegische Nostalgie für das Schicksal der Slawen, in der sich elegische Töne der Traurigkeit mit pathetischen und rhapsodischen Aufrufen zum Handeln in Bezug auf „die erbliche Rolle der Nation“ abwechseln. Ihre glorreiche Vergangenheit und ihre unglückliche Gegenwart werden hier gegenübergestellt. Gleich die ersten beiden Strophen: Die riesigen eingedeutschten Gebiete der ehemaligen polabischen Slawen, einst die Wiege, heute der Sarg der ursprünglich dort lebenden Völker, über die man nicht anders kann, als zu weinen – dieser Eingang verkündet sofort das Programm und den Ton des Stücks . Die slawische Welt präsentiert sich als gedemütigte, versklavte und langfristig kolonisierte Peripherie der westlichen, insbesondere germanischen Welt. Der Dichter plündert den Sklavenhalter, das „neidische Teutonia“, also Deutschland, das ihnen viel Unrecht getan hat. „Schäme dich, neidische Teutonia, Nachbarin der Herrlichkeit, deine Hände haben viele dieser Sünden begangen.“ Die Antwort auf die Anklage gegen die germanische Expansion ist eine Passage über Gerechtigkeit – eine Feier der Freiheit, die im Verszeilensatz „Er Wer selbst der Freiheit würdig ist, weiß jede Freiheit zu schätzen, er, wer Sklaven bindet, ist selbst ein Sklave.“ Für den Dichter sind die Erzfeinde der Slawen die Deutschen, die anderen Slawen – die Vorfahren. Menschen, die verblendet, unrein, falsch und ihres Namens unwürdig sind. Die Hoffnung für die Zukunft der Slawen ist Russland, symbolisiert durch das Motiv einer Eiche, um die sich seiner Meinung nach alle slawischen Nationen schließen sollten. Die elegischen Gesten in der Komposition werden nach und nach durch den Glauben an die humanistische Zukunft der Menschheit, einen appellierenden Aufruf zum Handeln und visionäre Bilder ersetzt: „Das größte Laster liegt im Unglück, und wer den Zorn des Himmels besänftigt, tut es besser.“ noch eine Zukunft haben: Selbsterkenntnis, Kultur und der feste Glaube, dass die Zeit, die Wunden verursacht, sie heilt, dass, wenn eine Nation in die Irre geht, sie nicht die ganze Menschheit in die Irre führen kann. „Die Zeit verändert alles, sogar die Zeiten, er führt die Wahrheit zum Sieg, was hundert fehlgeleitete Zeitalter beabsichtigt haben, die Zeit wird sich ändern – die Menschheit wird den richtigen Weg finden und nach hundert fehlgeleiteten Jahren wird sich die Zeit ändern und die Zeit wird sich ändern.“ prophezeite Kollár – der Prophet. Mit dieser Hoffnung schließen die Distichonen des Präludiums.

Stojí lípa na zeleném luze

plná starožitných pamětí,

ku ní, co jen přišlo podletí,

bývala má najmilejší chůze.

Žele moje, city, tužby, núze,

nosil jsem jí tajně k odnětí.

jedenkráte v jejím objetí

takto zalkám rozželený tuze:

„Ó ty, aspoň ty již, strome zlatý,

zastiň bolesti a hanobu

lidu toho, kterému jsi svatý!“

Tu dech živý v listí hnedky věje,

peň se hne a v božském způsobu

Slávy dcera v rukách mých se směje.

Stojí lipa na zelenej stráni,

v jej pamäti – dávnoveká diaľ.

Sotva prišlo leto, smeroval

som na svojich prechádzkach v tie strany.

Svoje žiale, city, túžby, plány

tajne som tej lipe zveroval.

Raz, keď ma až príliš mučil žiaľ,

zvolal som, jej lístím objímaný:

„Ó, aspoň ty, strom môj zlatokvetý,

na bolesť a hanbu vrhni tieň –

trpí ňou ľud, ktorému si svätý!“

Vtom živý dych z toho lístia veje,

ako zázrakom sa pohne kmeň –

dcéra Slávy v rukách sa mi smeje.

ZÁLA

„Na,“ řku, „jednu vlasti půlku, druhou Míně.“

Základom spevu Zála sa stal prvý oddiel časti Znělky neb sonety z Básní Jana Kollára z roku 1821, ktorý obsahoval znelky tematicky sa viažúce na Kollárov pobyt v Jene. Spev začína mytologicky stvárneným momentom „zrodu“ Míny. Ako náhradu za minulé krivdy, dlhými vekmi na Slovanstve páchané, na ktoré si sťažuje bohyňa Sláva, slovanský Olymp stvorí ideál novej slovanskej devy. Táto božská dcéra Slávy, súhrn predností všetkých slovanských kmeňov, pripadne ako náhrada zarmútenému básnikovi a zároveň i ťažko skúšanému Slovanstvu. Mína sa stáva milenkou básnika, jeho múzou a zároveň symbolom celého slovanstva. Sprevádza ho po nemeckých krajoch, kedysi obývanými Slovanmi. Básnik sa vyznáva zo svojej lásky k nej a skladá jej sľub večnej lásky. V závere spevu sa pred básnikom zjavujú poslovia vlasti

a lásky. Dochádza k riešeniu otázky vzťahu osobného a nadosobného. Na otázku duchov s mečom odpovedá: „Mlčím, váham: rázem rukou v ňadru sáhnu, srdce vyrvu, nadvé rozlomím: „Na,“ řku, „jednu vlasti půlku, druhou Míně.“ Básnik tak priam ikonicky rozlamuje srdce na dve polovice, čím nadlho osloví aj inšpiruje nasledujúce generácie básnikov. Ním začína v Slávy dcere silnieť nadosobná, národno – vlastenecká tematika a nastáva osudové lúčenie básnika s Mínou. Obracia sa za zálskym údolím, za farou v Lobede, za strateným „miestom utešeným“, kde prežíval slastné, opojné chvíle. A my sa obraciame za Kollárom. Vidíme ho nasýteného kultúrou zlatého veku nemeckojazyčnej kultúry. Klasickej i romantickej. Tak, ako ju on poznal v posvätnom trojuholníku Jena – Weimar – Wartburg. Vidíme ho zblížiť sa prostredníctvom tejto kultúry s kultúrou európskou. Od Danteho a Petrarcu, cez Shakespeara po estetickú hru romantikov.

Auf Wiedersehen Nemecko! Vítejte (doma) v Čechách!

SAALE

The first section of the part titled Tunes or Sonnets from Jan Kollár’s Poems from 1821, which contained tunes thematically related to Kollár’s stay in Jena, became the basis of song Saale. The song begins with a mythologically rendered moment of the „birth“ of Mína. As a compensation for the past wrongs, perpetrated on Slavs for ages, which the goddess Sláva complains about, the Slavic Olympus creates the ideal of a new Slavic maiden. This divine daughter of Sláva, the sum of the virtues of all the Slavic tribes, will be the substitute for the sorrowing poet and of the sorely tried Slavs. Mína becomes the poet’s mistress, his muse and, at the same time, the symbol of all Slavicity. She accompanies him on his journey through the German lands once inhabited by Slavs. The poet confesses his love for her and promises his eternal love to her. At the end, messengers of homeland and love appear in front of the poet. The question of the relationship between the personal and the super personal is addressed. He replies to the question of the ghosts with the sword: „I am silent, I hesitate: I strike my hand in my chest, I tear out my heart, I break it in two halves: „Here,“ I say, „one half to my country, another one to Mína.“ The poet thus iconically breaks his heart into two, which will long appeal to and inspire following generations of poets. With this act, the super personal, national-patriotic theme begins to grow stronger in The Daughter of Sláva and the poet’s fateful farewell to Mína occurs. He turns back to the Saale valley, to the parish in Lobeda, to the lost „place of comfort“ where he had experienced pleasurable, intoxicating moments. And we look back at Kollár. We see him saturated with the culture of the golden age of German-speaking culture. Both classical and romantic. As he got to know it in the sacred triangle of Jena – Weimar – Wartburg. We see him coming closer to the European culture through this culture: from Dante and Petrarch, through Shakespeare to the aesthetic play of the romantics.

Auf Wiedersehen Germany! Welcome (home) to Bohemia!

ZÁLA

Die Grundlage des Gesangs Zála bildete der erste Abschnitt des Teils „Znělky neb sonety“ aus den Gedichten von Ján Kollár aus dem Jahr 1821, der Lieder thematisch bezogen auf Kollárs Aufenthalt in Jena enthielt. Der Gesang beginnt mit dem mythologisch gestalteten Moment der „Geburt“ von Mína. Als Ersatz für vergangene Unrechte, über lange Jahrhunderte an den Slawen begangen, auf die sich die Göttin Sláva beklagt, erschafft der slawische Olymp das Ideal einer neuen slawischen Jungfrau. Diese göttliche Tochter der Sláva, die Summe der Vorzüge aller slawischen Stämme, wird dem traurigen Dichter und zugleich dem schwer geprüften Slawentum als Ersatz zuteil. Mína wird zur Geliebten des Dichters, seiner Muse und zugleich zum Symbol des gesamten Slawentums. Sie begleitet ihn durch deutsche Gebiete, die einst von Slawen bewohnt wurden. Der Dichter gesteht seine Liebe zu ihr und schwört ihr ewige Liebe. Am Ende des Gesangs erscheinen vor dem Dichter die Boten des Vaterlandes und der Liebe. Es kommt zur Klärung der Frage nach dem Verhältnis des Persönlichen und des Überpersönlichen. Auf die Frage der Geister mit dem Schwert antwortet er: „Ich schweige, zögere: plötzlich greife ich mit der Hand in die Brust, reiße das Herz heraus, breche es entzwei: Hier, sage ich, eine Hälfte für das Vaterland, die andere für Mína.“ Der Dichter bricht so sein Herz ikonisch in zwei Hälften, womit er auch die folgenden Generationen von Dichtern ansprechen und inspirieren wird. Mit ihm beginnt in der Tochter der Sláva die überzeitliche, national-patriotische Thematik zu stärken und es kommt zur schicksalhaften Trennung des Dichters von Mína. Er wendet sich vom Zála-Tal, vom Pfarrhof in Lobeda, vom verlorenen „Trostort“ ab, wo er selige, berauschende Momente erlebte. Und wir wenden uns Kollár zu. Wir sehen ihn gesättigt mit der Kultur des goldenen Zeitalters der deutschsprachigen Kultur. Klassisch und romantisch. So wie er sie im heiligen Dreieck Jena – Weimar – Wartburg kannte. Wir sehen ihn sich durch diese Kultur der europäischen Kultur nähern. Von Dante und Petrarca, über Shakespeare bis zum ästhetischen Spiel der Romantiker.

Auf Wiedersehen Deutschland! Willkommen (zu Hause) in Böhmen!

Pracuj každý s chutí usilovnou

na národu roli dědičné,

cesty mohou býti rozličné,

jenom vůli všichni mějme rovnou.

Bláznovství jest chtíti nemistrovnou

rukou měřit běhy měsíčné,

jako k plesu nohy necvičné

pokoušeti pro pochvalu skrovnou.

Lépe činí ten, kdo těží s málem,

stoje věrně na své postati,

velkýť je, buď slouhou, nebo králem:

často tichá pastuchova chyžka

více pro vlast může dělati

nežli tábor, z něhož válčil Žižka.

Pracuj každý s usilovnou chuťou

na dedičnej roli národa,

rôzne cesty pozná príroda,

no spoločná vôľa – naše puto.

Len blázon beh luny nezvyknutou

rukou meria – veď sa neoddá

nohy, čo sa na ples nehodia,

pre pár pochvál do tanca hnať kruto:

lepšie robí ten, čo vyjde s málom,

verne lipne k rodnej postati,

veľký, či je sluhom a či kráľom.

Často tichá pastierova chyžka,

otčina, viac slávy chystá ti

než tábor, čo z neho tiahol Žižka.

LABE

„Do zlých časů, Bůh to z nebe vidí, naše živobytí upadlo.“

Cesta do vlasti tvorí rámec druhého spevu Labe. Uplatnenie v ňom našla väčšina vlastenecky ladených zneliek, ktoré kvôli cenzúre nemohli byť publikované v Básňach z roku 1821. V druhom speve sa prelína slovanská prítomnosť s minulosťou a budúcnosťou. Prítomnosť je priesečníkom medzi minulosťou a budúcnosťou. V tomto priesečníku láska, básnikovo ľúbostné opojenie k Míne patrí do minulosti. Ľúbostné motívy sa vyskytujú len v spomienkach, reminiscenciách a v „sprítomňovaní“ prežitých chvíľ. Intímna lyrika ustupuje poézii vlasteneckej. Básnik po ceste z Nemecka prichádza do krajiny Slovanov, do Čiech. Spoznáva pamätné miesta národnej histórie, ospevuje krásu českého jazyka, sprítomňuje a oživuje postavy z národnej minulosti, vyzýva Slovanov k jednote: „Nechte svár, co hrob již vlasti vyryl, slyšte národ, ne křik Feaků, váš je Hus i Nepomuk i Cyril.“ Dôraz kladie na morálku – stáva sa hlásateľom mravných zásad. Smeruje k výchove k činorodému vlastenectvu. Apeluje na spolurodákov, vyzýva ich k činorodej práci pre blaho národa. Vlasť a národ v básnikovom ponímaní predstavujú posvätné hodnoty: „Však znám draka s tváří černochudou, proti němuž tyto úlomky hříchů ještě sněhu bělší budou; ten sám loupí, repce, učí zlému, bije sebe, předky, potomky a zní: nevděk ku národu svému.“ Myšlienky hriešnosti, prameniace z nevďačnosti k národu zopakuje: „Nepřipisuj svaté jméno vlasti kraji tomu, v kterém bydlíme, pravou vlast jen v srdci nosíme…“ Práca na „národa roli dedičnej,“ ktorá ako jediná môže prispieť k povzneseniu národa, je vyjadrená slovami: „Pracuj každý s chutí usilovnou na národu roli dědičné, cesty mohou býti rozličné, jenom vůli všichni mějme rovnou.“ Prežívanie nielen vlastnej citovej drámy, ale aj skepsu človeka nad pohnutou dobou básnik komentuje: „Do zlých časů, Bůh to z nebe vidí, naše živobytí upadlo.“ A keď národní buditelia: „našli prázdnou pustotu, kterou netklo žádne ještě rádlo,“ odhodláva sa k namáhavej úlohe, „aby svět byl, kde nic předtím vládlo.“

No a teraz poďme dolu, k Dunaju – „domov,“ do Uhorska!

Spomienky na stratenú lásku opäť sa vracajú.

ELBE

The journey to his homeland forms the framework of the second song titled Elbe. Most of the patriotic tunes, which could not be published in the Poems in 1821 due to censorship, can be found here. In Elbe, the Slavic presence intertwines with the past and the future. The presence is the intersection between the past and the future where love, the poet’s amorous infatuation with Mína, belongs to the past. Love motifs occur only in memories, reminiscences and in the „recollection“ of experienced moments. Intimate lyricism gives way to patriotic poetry. After a journey from Germany, the poet arrives in Bohemia, the land of the Slavs. He recognises memorable places of the national history, celebrates the beauty of the Czech language, recalls and revives figures from the national past and calls the Slavs to unity: „Leave the strife that has already engraved the grave of the homeland, hear the nation, not the cries of the Feaks, yours is Hus and Nepomuk and Cyrilius.“ Kollár emphasises morality as he becomes a proclaimer of moral principles. He directs towards education for the sake of active patriotism. He appeals to his compatriots, calling them to work hard for the welfare of the nation. Homeland and nation in the poet’s conception represent sacred values: „For I know a dragon with a black and skinny face against whom these fragments of sins will be whiter than snow; he himself robs, beets, teaches evil, beats himself, ancestors, descendants and sounds: ingratitude to his nation.“ The thoughts of sinfulness, springing from ingratitude to the nation, he repeats, „Ascribe not the holy name of fatherland to the land in which we dwell; we bear the true fatherland only in our hearts…“ The work on „the nation’s hereditary role,“ which alone can contribute to the upliftment of the nation, is expressed in the words: „Work everyone with the will to work hard on the nation’s hereditary role, the paths may be different, but let’s all work equally hard.“ Experiencing not only his own emotional drama, but also the scepticism of a man over the troubled times, the poet comments: „Into evil times, God sees it from heaven, our livelihood has fallen.“ And when the national revivalists „have found the empty wasteland untouched by any plough yet” he commits himself to the arduous task of „making the world where nothing had ruled before.“

And now let’s go down to the Danube – „home“, to Hungary! The memories of the lost love return again.

LABE

Die Reise in die Heimat bildet den Rahmen des zweiten Gesanges Labe. Darin fanden die meisten patriotisch gestimmten Lieder Anwendung, die aufgrund der Zensur nicht in den Gedichten von 1821 veröffentlicht werden konnten. Im zweiten Gesang verweben sich slawische Gegenwart mit Vergangenheit und Zukunft. Die Gegenwart ist ein Schnittpunkt zwischen Vergangenheit und Zukunft. In diesem Schnittpunkt gehört die Liebe, das liebestrunkene Entzücken des Dichters für Mína, der Vergangenheit an. Liebesmotive treten nur in Erinnerungen, Reminiszenzen und im „Vergegenwärtigen“ erlebter Augenblicke auf. Intime Lyrik weicht der patriotischen Poesie. Auf dem Weg aus Deutschland kommt der Dichter in das Land der Slawen, nach Böhmen. Er erkennt bedeutsame Orte der nationalen Geschichte, besingt die Schönheit der tschechischen Sprache, vergegenwärtigt und belebt Figuren aus der nationalen Vergangenheit und ruft die Slawen zur Einheit auf: „Lasst den Streit, der schon das Grab der Heimat gegraben hat, hört, Volk, nicht das Geschrei der Phäaken, euer ist Hus und Nepomuk und Cyrill.“ Er legt Nachdruck auf die Moral – er wird zum Verkünder moralischer Prinzipien. Er strebt nach einer Erziehung zu aktivem Patriotismus. Er appelliert an seine Landsleute, ruft sie zur aktiven Arbeit für das Wohl der Nation auf. Heimat und Volk stellen in der Vorstellung des Dichters heilige Werte dar: „Doch ich kenne den Drachen mit dem finsteren Gesicht, gegen den diese Scherben der Sünden noch weißer als Schnee sein werden; der selbst raubt, mault, zum Bösen lehrt, sich selbst, die Ahnen, die Nachkommen schlägt und ruft: Undank gegenüber seinem eigenen Volk.“ Die Gedanken der Sündhaftigkeit, die aus der Undankbarkeit gegenüber dem Volk entstehen, wiederholt er: „Schreibe dem heiligen Namen der Heimat nicht jenen Ort zu, in dem wir wohnen, die wahre Heimat tragen wir nur im Herzen….“ Die Arbeit an der „ererbten Rolle des Volkes“, die allein zur Erhebung der Nation beitragen kann, wird ausgedrückt mit den Worten: „Jeder arbeite mit eifriger Lust an der ererbten Rolle des Volkes, die Wege können unterschiedlich sein, nur den Willen lasst uns alle gleich haben.“ Das Erleben nicht nur des eigenen emotionalen Dramas, sondern auch die Skepsis des Menschen angesichts der bewegten Zeit kommentiert der Dichter: „In schlechte Zeiten, Gott sieht es vom Himmel, ist unser Lebensunterhalt gefallen.“ Und als die nationalen Weckrufer „eine leere Öde fanden, die noch kein Pflug berührt hatte“, entschließt er sich zur mühsamen Aufgabe, „dass die Welt sein möge, wo zuvor nichts herrschte.“

Nun aber lasst uns hinabsteigen, zur Donau – „Heimat“, nach Ungarn! Erinnerungen an die verlorene Liebe kehren wieder zurück.

Dunaji, ty i všech toků kníže,

i všech Slávů děde nádherný,

proč jsi vzniku svému nevěrný,

v cizí moře pěkné vlny hříže?

Více-li tě, nežli Osman, víže

čisté lásky osud mizerný,

obrať zpátkem běh svůj stříberný

a nes k cíli slzy tyto blíže.

Chceš-li sobě chvály věnce plésti,

věz, že není menší oslava

slzu jednu a sto lodí nésti.

Však i zisk tě čeká, nejen chvála:

tu ti jako bratru Vltava,

tam jak choti v náruč padne Zála.

Oj, ty Dunaj, dedo všetkých Slávov

a knieža riek, prečo nádherný

tvoj prúd prameňu je neverný –

cudzie more plniť nemáš právo.

Ak ti viac než Turci vŕta hlavou

láska a jej osud mizerný,

obráť späť svoj prúd a zober mi

slzy k nej – ty dokážeš to hravo.

Ak máš dušu po chvále smädnú,

vedz, že rovnaká je oslava

za sto lodí i za slzu jednu.

No aj zisk ťa čaká, nielen chvála –

tu ťa ako brata Vltava,

tam zas ako muža prijme Sála.

DUNAJ

„Šťastnou tedy cestu, básně, jdouce neste pozdravení Slovanům“

V treťom speve básnik ukončil svoju cestu. Prichádza na Slovensko symbolizované obrazmi hluchých Tatier a mŕtveho Dunaja. Smútok nad osudom básnikovej lásky sa prekrýva so smútkom nad osudom jeho vlasti. Mína je vzdialená, žije už len v básnikovych blednúcich spomienkach. Básnik stráca nádej, že sa jeho láska k milovanej osobe naplní počas pozemského života. Jeho túžba sa upiera na stretnutie s ňou vo večnosti: „Tam, kde mutné vyschnou časů řeky, kde choť sestra jedno znamená: tam jsem tvá a ty můj po vše věky.“ Vzýva smrť, aby ho zbavila pozemského trápenia a „strastí těchto žaláře“. Lúči sa so svojou láskou, lúči sa aj s poéziou: „Již se s tebou, Múzo, rozžehnávám, spolkyně mých zpěvů truchlivých, již ti lyru z rukou loučivých vracím a dík za tvou půjčku vzdávám.“ V odhodlaní vzdať sa mladíckeho prežívania ľúbostných citov, odovzdáva poetický nástroj – lýru a píšťalu do rúk múzy, aby ju vymenil za harfu – symbol vyzretosti poézie a básnického génia: „Ty, co kráčíš zpěvnějšími kraji, proměň nástroj, po hře mládenčí, v harfu a veď z Pindu na Sinaji.“ Odchod z Pindu na Sinaji, z Apollónovho kraja lásky a krásy na biblickú horu Mojžišovu, na ktorej dal Mojžiš izraelskému národu desať božích prikázaní, symbolizuje básnikov posun od „mládeneckej“ ľúbostnej poézie k reflexiám nadosobným. Celú skladbu prvej verzie Slávy dcery Kollár uzatvára záverečnou znelkou, z ktorej jasne zaznieva princíp tolerancie a porozumenia: „Šťastnou tedy cestu, básně, jdouce neste pozdravení Slovanům, všechněm vůkol, zvláště Tatranům, a pak Čechům, jejich dcerky jsouce.“

Zavŕšila sa pôvodne trojdielna kompozícia Slávy dcery. Jej bázou sa stal znelkový cyklus publikovaný v Básňach Jana Kollára (1821), odkiaľ viedla cesta k prvej 150 sonetovej verzii roku 1824. Jej textový vývoj pokračoval k úplnému vydaniu z roku 1832, s názvom Slávy dcera. Báseň lyricko-epická v pěti zpěvích. Básnickú skladbu Kollár doplnil o dva nové spevy Léthé (slovanské nebo) a Acheron (slovanské peklo). Spolu s novým vydaním Slávy dcery vydal Ján Kollár komentár s vysvetlivkami Výklad čili Přímětky a vysvětlivky ku Slávy dceře.

DANUBE

DONAU

Im dritten Gesang beendet der Dichter seine Reise. Er kommt in die Slowakei, symbolisiert durch die Bilder der stummen Tatra und der toten Donau. Die Trauer über das Schicksal der Liebe des Dichters überschneidet sich mit der Trauer über das Schicksal seines Landes. Mína ist fern, sie lebt nur noch in den verblassenden Erinnerungen des Dichters. Der Dichter verliert die Hoffnung, dass seine Liebe zu der geliebten Person im irdischen Leben erfüllt wird. Sein Verlangen richtet sich auf ein Treffen mit ihr in der Ewigkeit: „Dort, wo die trüben Flüsse der Zeiten austrocknen, wo Gattin Schwester eins bedeutet: dort bin ich dein und du mein für alle Ewigkeit.“ Er ruft den Tod, um ihn von irdischem Leiden und „den Qualen dieses Kerkers“ zu befreien. Er verabschiedet sich von seiner Liebe, er verabschiedet sich auch von der Poesie: „Nun verabschiede ich mich von dir, Muse, Verschlingerin meiner traurigen Lieder, gebe dir die Leier aus scheidenden Händen zurück und danke dir für dein Darlehen.“ Im Entschluss, das jugendliche Erleben der Liebesgefühle aufzugeben, übergibt er das poetische Instrument – die Leier und die Flöte – in die Hände der Muse, um sie gegen die Harfe zu tauschen – Symbol der Reife der Poesie und des poetischen Genies: „Du, der du durch melodischere Gefilde wandelst, tausche das Instrument nach dem jugendlichen Spiel, in eine Harfe und führe von Pindus nach Sinai.“ Der Abgang von Pindus nach Sinai, von Apollos Land der Liebe und Schönheit zum biblischen Berg Moses, auf dem Moses dem israelitischen Volk die zehn Gebote gab, symbolisiert den Übergang des Dichters von der „jugendlichen“ Liebespoesie zu Reflexionen über das Überpersönliche. Die gesamte Komposition der ersten Version der Tochter der Sláva schließt Kollár mit einer abschließenden Znelka ab, aus der der Grundsatz der Toleranz und des Verständnisses deutlich erklingt: „Glückliche Reise also, Gedichte, gehend bringt Grüße an die Slawen, allen ringsum, besonders den Tatra-Leuten, und dann den Tschechen, ihrer Töchter.“

Damit endet die ursprünglich dreiteilige Komposition der Tochter der Sláva. Ihre Basis wurde der Znelka-Zyklus, veröffentlicht in den Gedichten von Ján Kollár (1821), von wo aus der Weg zur ersten 150-Sonett-Version von 1824 führte. Ihre textliche Entwicklung setzte sich fort zum „vollständigen“ Ausgabe von 1832, mit dem Titel Tochter der Sláva. Ein lyrisch-episches Gedicht in fünf Gesängen. Kollár ergänzte das poetische Werk um zwei neue Gesänge Léthé (slawisches Nebel) und Acheron (slawische Hölle). Zusammen mit der neuen Ausgabe der Tochter der Sláva veröffentlichte Ján Kollár einen Kommentar mit Erläuterungen Erklärung oder Bemerkungen und Erläuterungen zur Tochter der Sláva.